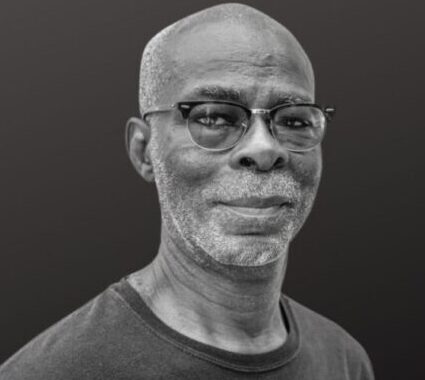

On Bola Ahmed Tinubu

Last Monday, All Progressives Congress chieftain and one-time governor of Lagos State, Bola Tinubu, was inaugurated President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Mr Tinubu’s inauguration was indexed in Nigerian law, which I acknowledge and respect. The ongoing legal challenges to his election are also indexed in the law, and I am happy to acknowledge them as well.

Just so it is clear, this column will be engaging with Mr Tinubu’s time under a simple understanding: while he now holds the yam and the knife, the yam is rotten, and the knife, poisoned. And because he has a role in the putrid condition of the dinner table, I am doubtful that he is man enough to make a success of serving the Nigerian people.

There are two broad reasons for his quandary. The first is the objective state of the country, in terms of its multiplicity of mutating challenges, his APC party, and his predecessor, Muhammadu Buhari. The second is Tinubu himself.

I begin with the first. Tinubu inherits a country that, particularly now that he has had one week to receive official briefings, everyone recognises as a mess. For eight years, and between Buhari’s laziness and his sole focus on himself (“I got what I wanted,” he confessed), every aspect of Nigerian life deteriorated deeply while the nation plunged into poverty and debt.

No, Buhari did not really understand much of it, did not care beyond himself and his grudges for being sacked from leadership in 1983, and did not understand the concepts of true achievement or patriotism. He was reluctant to apply himself to issues that were challenging. He did not like intellectuals, perhaps because they reminded him of his insecurities; preferring those with whom he shared affinities that were unrelated to the broader interest. It is unclear if he ever saw or read a single book in his eight years in Aso Rock.

This is simply why the bus Buhari was driving was already in the ditch within months of May 2015, and why there is no sector of Nigerian reality today that he did not make worse. He even made the Peoples Democratic Party look decent.

APC, sadly, was worse than Buhari. It was a pathetic liar, as its own manifesto testified over the Buhari years. As if it was not already large enough as a gathering of crooks, for a part of Buhari’s first term, APC’s objective became to lure in the filthiest crooks in the party they had defeated. “Once you join APC, your sins are forgiven,” wasthe fishing line of the-then chairman, Adams Oshiomhole. Nigerians understood, and APC proved them right: the crooks thus recruited became saints.

To prove the point, Tinubu was still navigating his inauguration address last week when Buhari’s sewage backed up on him the moment he uttered three words: “subsidy is gone.” Within the hour, its reverberations were already being felt in petrol stations and markets nationwide. Those three words may yet define his entire presidency, no matter how long it lasts.

Buhari, from his indolence to his aloofness to his incompetence to his self-absorption, left a lot of landmines for his successor, whoever that was. Taking them on will be no easier for Tinubu simply because he is also of the APC.

That leads me to Tinubu himself. The new Nigerian leader may have taken the oath of office, but he did not win the election.

He knows this to be the truth, as do those who are closest to him. Some observers were so disgusted with what the so-called “independent” electoral commission called a credible contest they vowed never to return to Nigeria on future election-monitoring duties. The electoral commission did Tinubu no favours by its violation of the law and its own rules, and its hasty declaration of a winner.

On the other hand, perhaps that was the very idea: declare a victory that cannot be defended by the law or the facts, and challenge anyone who objects to mount a legal challenge.

That legal challenge is now in process. Unlike in the past, the current challenge is more robust and the evidence far more engaging.

This is a situation where it is the electoral commission, not Tinubu, that is on trial, although as the principal beneficiary of the commission’s work, Tinubu is evidently the most at risk.

What such an award to the APC candidate accomplished was to extend the bizarre Tinubu story where, with him, nothing is straightforward, and controversy is standard.

Tinubu is now perhaps the best-known politician to come out of Nigeria, but that is not because of his record of service or his accomplishments or his smarts or his oratory, but because of controversies wherever he has been, and whatever he has done.

Those controversies centre on his character, or lack of it, and will yield great doubts as to his mission and his motive, and therefore his ability to serve the popular interest. This character question, which is an embarrassment to many Nigerians, will have a restraining impact not only on public policy, but on policy implementation.

Recently, for instance, Tinubu broached the c-word: corruption, the evil enterprise on which Nigeria floats, declaring that he will fight it. While it is always a good pledge to hear, no Nigerian leader has demonstrated the will and each of them, including the lion from Daura which turned out to be a mouse, buckled under it.

My personal belief is that Tinubu will be worse than all of them. He cannot and will not confront corruption. However, if he says he wants to fight it, let him deploy the power of personal example.

As a man who comes to the presidency burdened by doubt and an extremely negative public perception arising from his governorship of Lagos State and his “one-man democracy” in the state since then, he can allay fears by going beyond the provisions of the constitution and making his assets declaration public. That is the definition of goodwill and self-confidence. He must then compel his ministers and special advisers also to obey the law and declare their assets.

Of equal importance, Tinubu, if he is man enough, must probe the Buhari Years. As a self-celebrated “anti-corruption fighter,” I am sure the former leader will not object to the examination of many of his policies and officials.

In this regard, Tinubu has already indicated that he will investigate that administration’s currency change this year. There are many more.

Of course, Tinubu can look the other way. He is expected to. But he must make up his mind whether to serve God or Mammon. The Buhari administration became part of the mess it claimed it came to resolve; Tinubu can also become a part of that mess, but he cannot get to it or to the people responsible for it unless he goes through the Buhari layer.

The challenge for Tinubu is whether he chooses right or wrong. If he chooses the right one, he can write an entirely new story for himself, one that Nigeria’s beleaguered people will celebrate, regardless Tinubu’s darker past. He may not have a long time.