Nigerian court didn’t want contested election case. It just defended the winner

Nigeria’s presidential election court last week upheld the result of the country’s controversial election in February, in which Bola Ahmed Tinubu of the ruling All-Progressives Congress (APC) party was voted president.

The appeals court’s ruling, made in a televised event on 6 September, is no surprise – the court traditionally sides with the president – but the manner in which it did so has done nothing to reassure suspicious voters or allay fears of vote rigging. If anything, it has further undermined trust in the country’s electoral body and Nigeria’s democratic process as a whole.

The petition to the court came from opposition candidates Atiku Abubakar of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) and Peter Obi of the Labour Party (LP), who came second and third, respectively. They challenged the election result over various issues, notably how the electoral results were transmitted.

The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), the government body that oversees elections in Nigeria, chose to use biometric devices to register voters in the February election. These devices should ensure there are no double votes or fake ballots, thereby boosting transparency and public confidence.

It was not a cheap decision. INEC purchased 200,000 Bimodal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS) tablets from Chinese manufacturer Shenzhen Emperor Technology at a cost of nearly $800 each – a total spend of $159m.

INEC also decided that it would transmit election results electronically in real time using its purpose-built INEC Result Viewing Portal (IReV) technology, first used in 2020. INEC chairman Mahmood Yakubu assured voters four months before the election that the expensive system was firmly in place and that his commission was “committed to ensuring that the 2023 general election is transparent and credible, reflecting the will of the Nigerian people”.

The problem is that Yakubu did not deliver on this promise.

INEC’s well-publicised election timetable had bundled the presidential contest of 25 February with that of the legislative elections to the Senate and House of Representatives. But while the results of those elections were transmitted electronically through IReV in the hours and days following the election, as advertised, the results of the presidential election curiously did not appear.

The electoral commission said there had been a glitch, and the results were compiled manually – as ballot papers were counted – over a tense four-day period. As fears mounted nationwide that the election might be rigged for Tinubu over Obi, who had been very popular with the youth and in a number of polls, INEC did indeed declare him the winner on 1 March. Even as the announcement was made, IReV failed to work.

Appeals court ruling

Few people could have expected the five-person court, headed by Justice Haruna Tsammani, to overturn the election result, but fewer still could have expected that the panel – first together, then one judge after another – would defend Tinubu’s election rather than adjudicate on the matter at hand.

You might expect the court to take an hour or two announcing its ruling. Perhaps three or four hours. But the tribunal took more than ten hours to deliver its verdict. The judges took turns admonishing the petitioners on technical issues, including the provision of specific documents that the petitioners had requested but could not pry out of the hands of INEC.

As well as comprehensively dismissing the petitions the opposition candidates had brought, the tribunal prohibited Obi from affirming that the 2023 elections violated the 2022 Electoral Act, and rejected the European Union Observation Mission’s final report, which held that: “The election exposed enduring systemic weaknesses and therefore signal a need for further legal and operational reforms to enhance transparency, inclusiveness, and accountability.”

The court also rejected the 18,088 blurred results sheet tendered by the petitioners, which they had printed as they appeared on IRev, saying they were not tied to any of the polling units to which the results referred – despite evidence presented in court to the contrary. It also said that INEC was under no obligation to tender election results electronically, and that no allegations of anomalies, malpractice or overvoting had been proven.

Within hours of the tribunal’s decision, Atiku and Obi indicated that they would be appealing the verdict to the Supreme Court. It is the right thing to do, because it is the law. Voters would also like to see that option explored for the record. But I do not expect a different fate in the higher court.

Within hours of the tribunal’s decision, Atiku and Obi indicated that they would be appealing the verdict to the Supreme Court. It is the right thing to do, because it is the law. Voters would also like to see that option explored for the record. But I do not expect a different fate in the higher court.

What is at stake in Nigeria – particularly at a time when military coups have resurfaced on the continent – is the question of integrity in the nation’s elections as an element in the faith of the people in their government.

In theory, voting is the most democratic way of choosing a candidate or policy. In Nigeria, a voter must apply for a Permanent Voter’s Card (PVC) to be able to participate in the electoral process. Getting registered is a rigorous process, and people are rewarded by that card being validated by the BVAS system, enabling them to vote. In February 2023, the PVC did not fundamentally fail, certainly not in most elections. Despite some delays, interruptions and even some violence, the elections can be deemed a success – at least by Nigerian standards.

Except in the presidential contest. This led to a controversial result that the appeals process appears to have complicated, with the court mounting for INEC and Tinubu a defence that they appeared to be unwilling or unable to make for themselves.

By its performance, the court appears to have erected an insurmountable legal standard for election challengers. If a petitioner cannot even assert that the conduct of an election violates the law, how do they frame their challenge or seek justice?

The unintended consequence for voters is that they are confronted with accepting an injustice they believe has taken place before their very eyes, and they may begin to doubt their place in the electoral process. Something is wrong in Nigeria’s management of its elections, and that includes the appeals process.

The time has come for a comprehensive review. I believe that the answer is for the electoral commission to operate in smaller, more efficient parts of the machine providing clearly defined services in the election process, perhaps with some civil society participation as well. This would help correct a situation where INEC is granted the power to do all things credibly, but fails to do so every four years.

Unless this is done, democracy in Nigeria may collapse under the weight of its own sins, with repercussions for both the country and Africa as a whole.

Originally published by opendemocracy.net

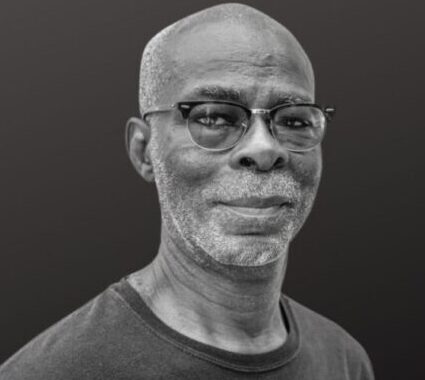

Image Source: | Olukayode Jaiyeola/NurPhoto via Getty Images