Destroy This Temple

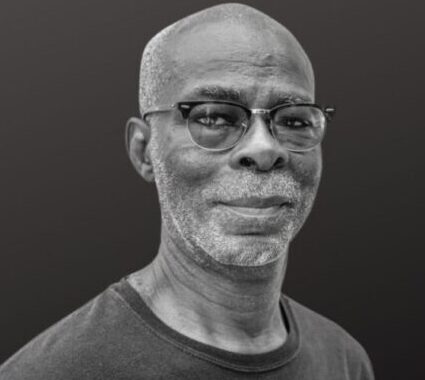

By

Sonala Olumhense

If you have ever used a Nigerian road, you are familiar with the experience of the motor vehicle breakdown requiring the intervention of a mechanic.

If you are lucky, there is one nearby. If your luck happens to be somewhere else, it may take hours—and a succession of mechanics, or days—to get that engine fixed, or the battery running again.

*Why is there no such facility for Nigerians to turn to when it comes to governance? Even the blind knows, or ought to know, that we have* *reached the point of no return.*

*Governance, for all practical purposes, is now simply a hoax. Nigeria is in the hands of people who pay, or* *are paid to pretend that achievement is possible or is in process: people who make, model, or manipulate* *hope for the public.*

Last week, the House of Representatives again signed into the hoax, claiming that it will institute “a comprehensive investigation into the controversial Lagos-Calabar Coastal highway project,” a project I have called “fiction” in this column, an enterprise which is simply audacious for its violations of law, ethics and practice.

The House of Representatives is a real institution. It is a powerful, legitimate body clearly described in Chapter Five of the constitution.

But the House, the business premises of which are in the Abuja Central District of the Federal Capital Territory, is a House of Mis-Representatives. As an institution, it is an irresponsible, uncommitted trading outfit that I have often denounced, along with the Senate, on this page.

The powers and responsibilities of the National Assembly are specified in the constitution. Its history and work are sadly not recorded, as Nigeria’s legislative bodies shamelessly take great care to maintain no archives.

For instance: to both the Senate and the House is granted the power to receive and consider the report of the Auditor-General of the Federation, every year: at least 22 such reports since 1999.

But there is no such record of receiving, by either House, let alone considering. In other words, there is no evidence that the Senators or the Representatives read the Auditor-General’s reports. The occasional outrage emerges only when they read media reports of the audit reports.

Even when the legislators loudly proclaim themselves to be busy on something, assignments are rarely completed or reports issued and archived.

Where, for example, is the House report of the Ad-hoc Committee of the House set up in 2017 to investigate the disappearance of the N11.1 billion budgeted for the State House Clinic under the administrations of Goodluck Jonathan and Muhammadu Buhari?

Where is the House report of the committee it said in 2020 would investigate the North-East Development Commission (NEDC) where over “N100 billion vanished in one year”?

Where is the report of the House ad hoc committee which investigated “the purchase, use, and control of arms, ammunition, and related hardware by Military, Paramilitary, and other Law Enforcement Agencies in Nigeria,” (alias looted arms funds)?

Where is the House report of the 2021 investigation of the N200bn Lokoja-Benin-City highway?

Where is the report of the Ad hoc Committee Probe of Recovered Looted Funds and Assets of Government (2002-2020), which included revelations of how the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation allegedly stashed $60 billion of public funds in the United States?

These few examples refer to work that the House claimed to have been doing. What about matters in which it looked in the other direction, such as the 2020 Buhari order to his Attorney-General, Abubakar Malami, to get rid of all assets that had been forfeited to the government.

I choose the term, “get rid off” as opposed to the “sell-off” which Buhari had used, because Nigerians were never informed as to whether anything was sold, let alone to whom or for how much. If anyone has any proof that privileged government officials did not simply distribute the assets among themselves, their families and cronies, they have told nobody.

The question is: why did the House never investigate Malami’s “Inter-Ministerial Committee on the Disposal of Federal Government of Nigeria’s Forfeited Assets,” to give Nigerians the confidence that Buhari’s patently corrupt government did not distribute the nation’s wealth among themselves on Abuja streets? In the end, were the assets really forfeited to Nigeria, or to the well-connected? Did the forfeiters become the “forfeitees”?

What did the House do when a newspaper revealed in 2019 that, according to the Auditor General of the Federation, a whopping N10.4 billion was paid in judgement debts in 2017 by the Ministry of Justice without due process?

This, then, is the House which says it will now investigate Nigeria’s most expensive and controversial public project in 64 years: the Lagos-Calabar Coastal highway.

But I can predict the future: if the House ever commences this endeavor, it will not complete it. If it completes it, it will not publish the report; and should it publish the report, it will not be archived.

To archive public information is to be a servant of history. The reason our officials maintain no records is that they consider themselves to be superior to history.

As important as Buhari thought he was, for instance, there is no archive of his presidency now available in Aso Rock.

Why is history important? Consider that only last week, Minister of Works Dave Umahi announced that the Bola Tinubu government will start the Abuja-Kano Road (AKR) soon, and complete it next year.

The Tinubu government is wrong: AKR is not a new road, and there is no question of its being “started.” It is part of the troubled A2 highway, and to the South, includes the Lokoja-Benin City stretch that Mr. Umahi recently said he would complete in six months.

The Buhari government laboured weakly on it for eight years, and I covered some of the story in January 2021, affirming that contrary to that government’s claims, it would not be completed until 2025. A lot of money, including part of the $308m Sani Abacha loot that was repatriated to Nigeria in 2020 by the US and the Island of Jersey, has been spent on it, those countries having Nigeria swear to it.

There is therefore no need for a new directive from Tinubu: In Fashola’s Town Hall in Kaduna in November 2020, as the Buhari government attempted to give the impression that 2023 was somehow possible, Julius Berger Managing Director Lars Richer put it simply: “The new deadline is now 2025.”

Remember: President Olusegun Obasanjo started the East-West Road in 2006. In late 2014, Mr. Jonathan signed the Lagos-Calabar rail project, which was renegotiated then approved by the Buhari government in 2021.

Also in 2015, Mr. Jonathan announced the National Integrated Infrastructure Master Plan, involving $2.9 trillion over 30 years; the road projects included Section V of the East-West, worth $1.07 billion, which was awarded to CCECC.

The Lagos-Calabar rail has now been abandoned by Mr. Tinubu in favour of a phantom Lagos-Calabar Road. That project is currently called ‘controversial,’ ahead of being called ‘abandoned.’

The Nigerian problem is not projects, it is people: those who people its governance, and those who cheer them on.

Where is that mechanic?