Oranges and Pennies

A few weeks ago, as is often the fate of Nigerians who encounter one-another outside our national borders, I found myself talking about the state of the nation with a friend who had emigrated from home several years ago. My assumption was that having both grown up in Lagos we would, broadly speaking, be starting with similar assumptions as we tried to make sense of the current political imbroglio. As it turns out, in this matter, we do not have a point of true north in common. He was convinced that there is something about the Nigerian in Nigeria, that makes efforts to change the culture of corruption in national affairs a futile exercise. “Jide,” he said “you may choose to ignore it but the fact is, that is who we are.” I replied, “Kunle my brother, do you think that there is something in the water, DNA or air of Nigeria that predisposes the Nigerian to selfish behavior?” He is about ten years younger than I am, so perhaps part of the parallax error between our points of view is one of time, not space. Anyway, to protect the guilty, I have changed his name.

The Lagos marina of the nineteen sixties, was not the concrete thoroughfare that it is today. It was a two-lane strip of tarmac that separated a row of department stores, Kingsway, UTC, Leventis and other specialist shops from the harbor. It would have been a corniche had Lagos Island not been below sea level. Elder Dempster the British shipping company, berthed its vessels MV Aureol, MV Accra and MV Apapa, the dream liners of their day, at the western end of the marina opposite the present location of the UBA head office. That area was known as the ‘quayside’, where seamen would regale pop-up audiences with gist and fabu about their exploits in distant lands. Quayside was a bustling melting pot of people and it had an allure of the forbidden. It was a market for exotic cigarettes like Gitanes, Gauloise, Lucky Strike and Camel; second hand clothing and no doubt other contraband that in those days I was too young to know anything about. Between you and me, it was here that I first caught a whiff of a pungent aroma that I would recognize later in life when I encountered it again. Moving eastward, in the direction of Force Road, beyond the CMS bus stop and the Cathedral Church of Christ, the shops gave way to colonial administrative buildings on the left of the road and coconut trees on the right, that arched out over the water’s edge.

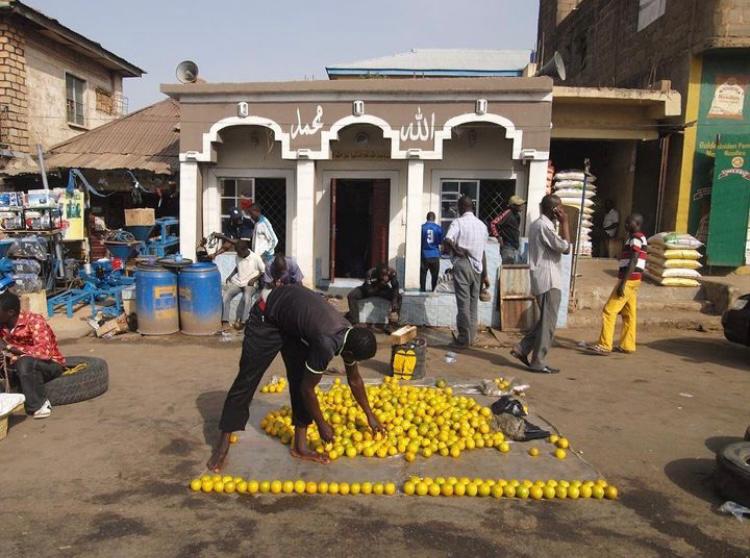

On the walk between quayside and Force Road, you would come across at least one basket of oranges on the ground next to which would be a pile of pennies. Everyone knew the price of an orange and would put down their toro meji or meta, take an orange and carry on. The seller did not come around until after sunset when he or she would collect their takings for the day and return the next morning with a fresh basket of oranges. “Not in the Lagos I know!” Kunle said, vehemently rejecting the idea that a period of trust had ever existed on those city streets, “You must have seen a different Lagos from mine.” His defining recollection of Lagos was the Babangida years, the era of the ‘evil genius’ with its spirit of every man for himself and the devil take the hindmost.

I know that we both experienced the same city, but indeed something had changed between the time that anchored my memory to it and his. The process of this change was barely noticeable, but it was fundamental to everything. I think that the change was in the understanding of the relationship between the individual and the larger society. The spirit of our interconnectedness creating community had been eroded. Gone was the subconscious awareness that if you take an orange without paying for it, you compromise the seller’s ability to put oranges out the next day when you are on the road and thirsty. So ultimately you do yourself no favor by not paying for the orange. The change took place all over the country and our national self-confidence is the major casualty. Self-confidence that has been replaced by empty bombast in most of our leaders, from whom we expect very little, and the servitude of many of the led, who ask very little of each other.

PS: As a parting shot, Kunle said that “it is only in Nigeria that people work so consistently against their own interests. When anything is scarce, the Nigerian will try to profit from the situation at the expense of others in the same boat as himself”. Though this victim blaming view is fairly widely held, I don’t think that it is true. One thing I know for sure though is that, as nonsensical as some of the things we do are, as soon as anyone starts saying only in Nigeria, I know that they have not looked elsewhere very closely. For example, we know that no sane person would struggle for anything on the shelf in a US supermarket, the supply chain keeps the shelves stocked or within a day of replenishment. When covid came along, and with it acute shortages of consumables, even in the richest countries, the behavior of many human beings faced with lack came to the fore. Selfish hoarding, battles for toilet paper at supermarkets and the yet unclear extent of the scale of corrupt disbursement of billions of dollars of pandemic economic support. This was triggered by the prospect of temporary uncertainty of supply and may give some insight into the behavior of people who live in a state of perpetual deprivation and uncertainty, as is the situation that the average Nigerian citizen is condemned to.